Talk of a Chinese housing bubble was deafening back in 2016. While few seemed to know exactly how much the prices have jumped, the spike during 2016 sparked concerns of China’s “hard landing”. So far, no bubble burst. But price growth did not stop either. Tighter liquidity measures, home purchase requirements and even a strict lockdown could not stop prices from inching up higher in major cities. Second-hand home prices in Shenzhen, for instance, grew 15.5% year-on-year in October 2020. Unlike housing bubbles which are inflated by household debt in some developed countries, China’s property boom emerges out of high savings and few investment alternatives. Prices are propped up by homeowners who trusted the government to protect their income-generating properties. Further price growth, however, is making housing out-of-reach for the country’s working adults and widening the gap between tech centres and rustbelt cities.

Lots of cash, nowhere to invest

While a slew of foreign direct investments (FDI) has kickstarted many countries’ paths to prosperity, China relied on high domestic savings to power its industrialisation. According to the World Bank and the OECD, China’s gross domestic savings have been above 30% since the 1970s and exceeded 40% in 2003. In Europe and the US, the figure hovers around 15-25%. With a small, volatile stock market and paltry interest rates, households have little means to combat inflation and prepare for retirement expenses. After the 2008 global financial crisis, wealth management products and fintech innovations such as online P2P lending became popular with their advertised high returns. As authorities are cracking down on the shadow banking sector which is supported by these products, however, more investors are looking elsewhere for an upside.

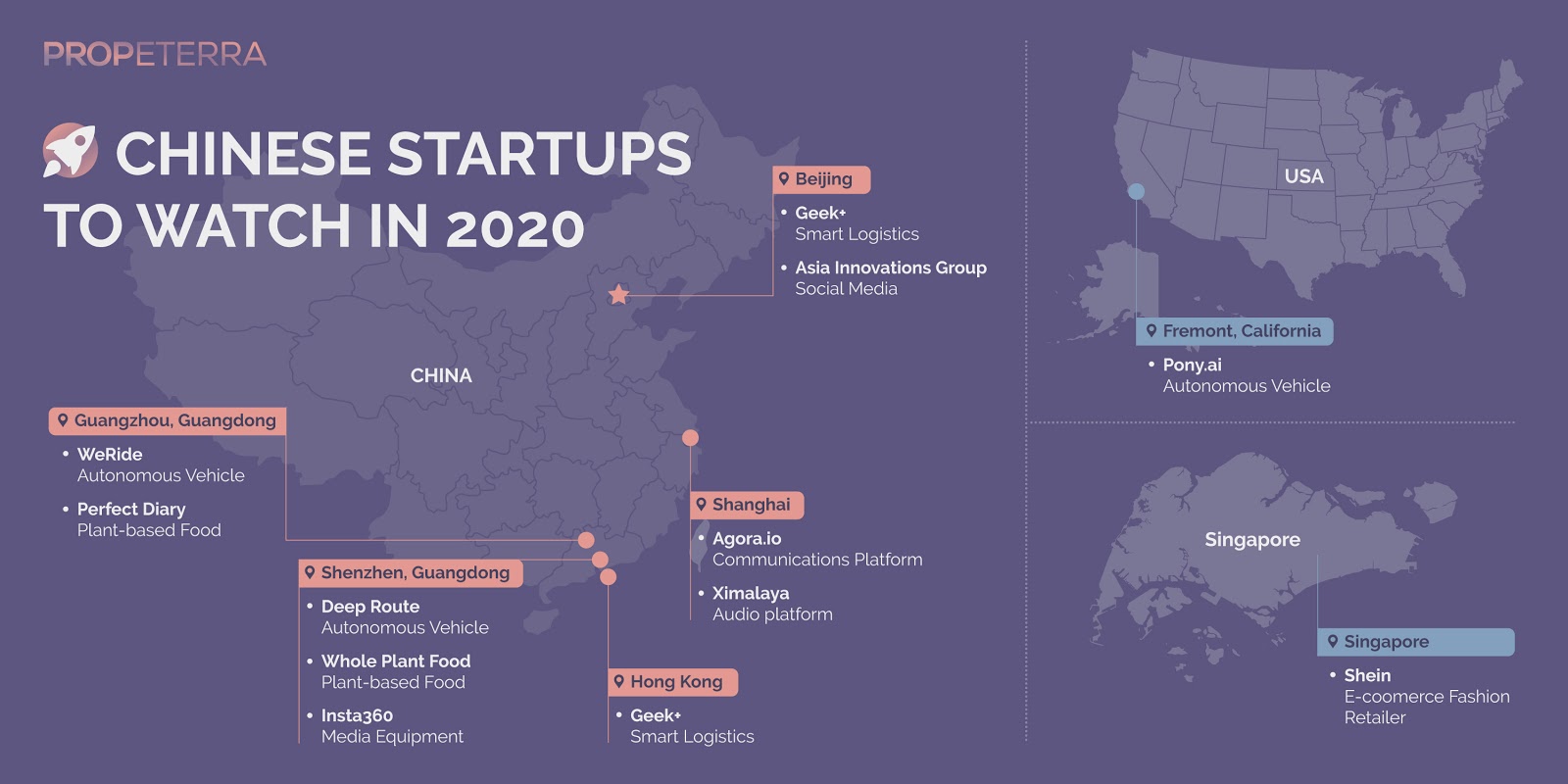

Price growth in China’s residential market has been accelerated by the country’s rapacious urbanization. In the last decade, factories gave way to services and IT firms which are bringing more population and consumption demands. It is not a coincidence that the biggest and up-and-coming startups (see map below) had their roots in the busiest cities. Firms in the knowledge-based economy start in/ move into cities to exploit externalities such as a vast talent pool and knowledge spillovers, a model proposed by Paul Krugman and other agglomeration theorists. Demand pushes up house prices and makes real estate an incredibly attractive opportunity, with at least a double-digit increase in Tier-1 cities.

Up-and-coming startups are all found China’s biggest metropolises

Up-and-coming startups are all found China’s biggest metropolises

Some think China has a booming real estate market because Chinese happen to love home ownership more than others. That cultural factor holds little sway when analysing the millennial population, who account for 65% of China’s consumption growth. It is no doubt that traditional Chinese culture values the idea of “settling down", which typically happens when someone stops drifting, starts a family and owns a home. In fact, millennial workers don’t like to be tied down. More 20s and 30s also chose to stay single and are not looking for houses to be “viable” for marriage. As authorities implemented more policies to boost the cap rate for rental unit developers and potential landlords, rental apartments/ co-living spaces became more trendy and lured millennials to rent rather than to buy.

Looking ahead: steady increase, rental investment potential, inequalities

China’s property boom is more of a structural imbalance than a fad or cultural behaviour. As long as uncertainty abounds and few investment alternatives are available, investors and households are likely to pour money into real estate. A recent poll done by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu found that after the lockdown, homeowners are more eager to purchase property than non-homeowners. The poll also found that households have become less confident in overseas property investment.

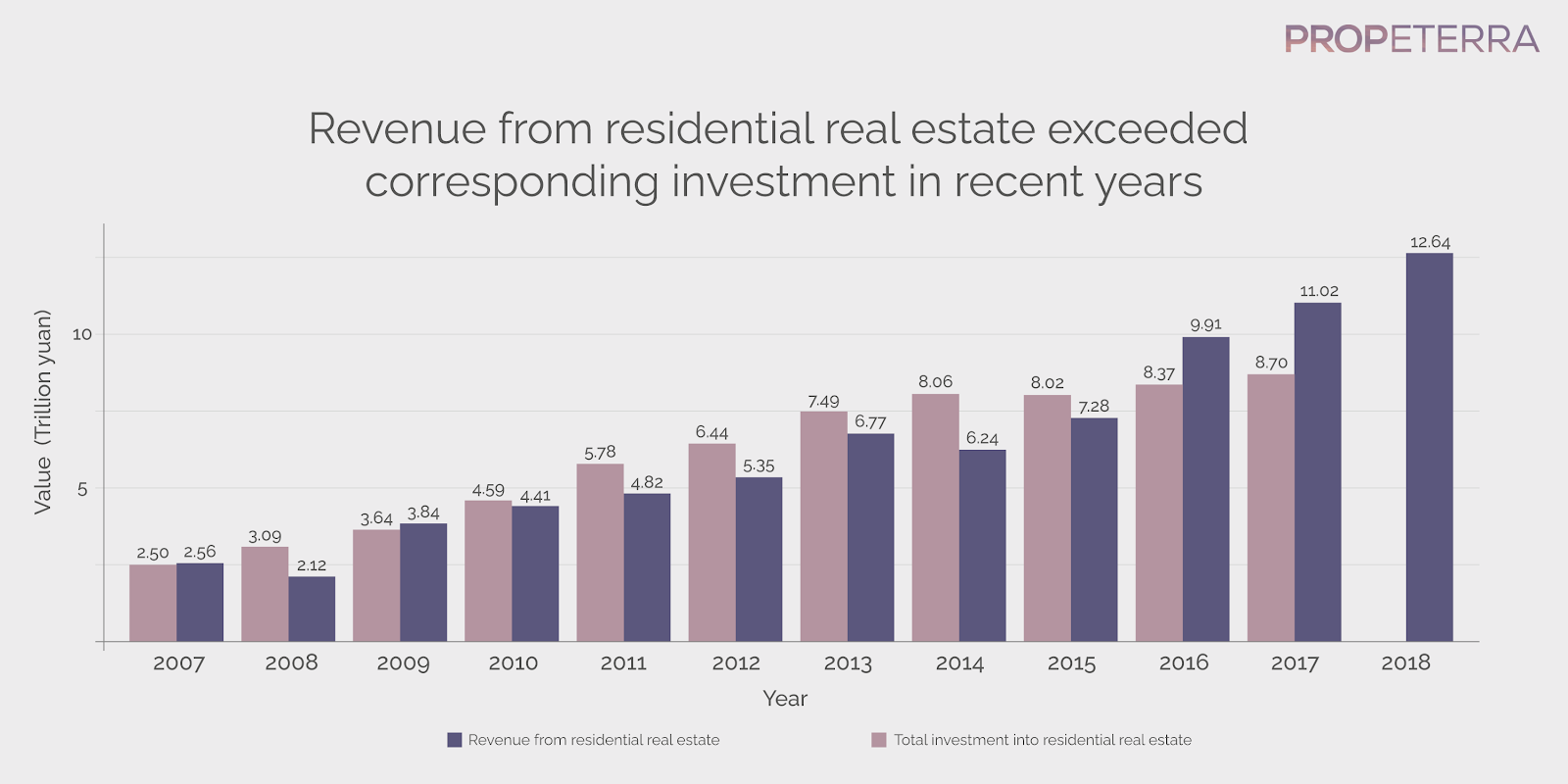

Revenue from residential real estate

Revenue from residential real estate

On the other hand, the political resolve to stabilize property prices is clear. Recent policies indicate that authorities are trying to make rental properties an investment alternative for citizens. If financial products such as REITS backed by rental income become attractive and rental yields increase with more millennials choosing to rent, profit from rental investments will grow and should be another area of attention for alpha seekers.

In a broader economic sense, China’s property boom is worrisome for the inequalities it creates. It is at least widening two gaps - that between homeowners and renters, as well as that between cities. Property prices in a few cities are even higher in terms of median income multiples than Hong Kong. A wealth gap would be destabilizing if it thwarts the aspiration of a middle class who has been more or less benefiting from the system thus far. Encouraging rentals will not make housing more affordable: In the past few years, co-living space operators such as Ziroom and 5I5J have pushed up urban rent by aggressively securing flats for refurbishment.

To top it off, the price rise is concentrated in cities which manage to draw investments and population. The so-called rust belt cities in the northeast provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang - the resource-dependent provinces - are actually declining in property prices because of shrinking population. The government has noted these “resource-depleted cities” and is set to tackle their decline, but signs of revival are yet to be seen.

With much uncertainty in the world market and confidence in the Chinese government, an overnight collapse of the country’s property market is well-nigh impossible. While it bodes well for property buyers, the financial risk becomes a socioeconomic problem as housing unaffordability and inter-city inequalities worsen. Equality is one of the core socialist values promoted by the Chinese Communist Party since 2012. A heavily-controlled capital market, however, is widening gaps between cities, property owners and renters. This is not to say neoliberalism solves it all, when almost all open market economies are dealing with populism catalysed by perceptions of inequality. It is in the party’s interest to make housing affordable and reverse city decline, but to do this without depending on the private sector, liberalising the market or upsetting homeowners would be a hard-pressed triple jump.

.jpeg)